The Latest At Valley Forge

Byron Harrod, CFO | Michele Clarke, CEO | Ron Clark, President | Bret Halley, COO

Welcome to the first edition of the Valley Forge newsletter, “Live Load”. We chose this name for the passion we have in load indicating fasteners and to represent the constant load information that can be captured on all fastener products Valley Forge & Bolt supplies, from our patented Maxbolts™ to the Clarkester™ system built to test for application loading with standard bolts.We plan for this to be our outlet to bring you interesting articles about load indicating fastener applications , technical updates on fasteners, upcoming events at Valley Forge and new developments in our Load Indicating Fasteners.

Welcome to the first edition of the Valley Forge newsletter, “Live Load”. We chose this name for the passion we have in load indicating fasteners and to represent the constant load information that can be captured on all fastener products Valley Forge & Bolt supplies, from our patented Maxbolts™ to the Clarkester™ system built to test for application loading with standard bolts.We plan for this to be our outlet to bring you interesting articles about load indicating fastener applications , technical updates on fasteners, upcoming events at Valley Forge and new developments in our Load Indicating Fasteners.

In 1974, Ron Clarke started Valley Forge & Bolt to service the mining industry. Through the years we have listened to our customers and what they have needed to make their bolted joint applications less problematic. In this way we have developed many patents which have become standard in industry.

Listening to the customer is one of our most important precepts. We focus on customer needs, their problems needing to be solved in bolting, and supply them with the best quality American made fastener. Throughout this time, we have been a small family owned business with Philomena Clarke running the sales department and Ron Clarke running engineering and production.

Now 40 years later, our second generation of bolt manufacturers is expanding operations and growing markets. We still have the same purpose: listen to the customer, find out what they need and supply them with the best. We have assembled a team of bolting professionals at Valley Forge with the same family ideals that Ron and Philomena instilled. In the months to come we will share information from many of these individuals and interesting application solutions. We hope you find this newsletter interesting and useful as you get to know Valley Forge and our capabilities.

Reprint Courtesy of The American Fastener Journal

| By Rix Quinn |

The year is 1947. The place is Jamalpur, India. Ron Clarke stands at a critical crossroads. His homeland has just become a sovereign country. Ron, just out of high school, is now independent, too. He needs to decide what to do with his long life ahead.

Already interested in engineering, Ron looks around for a place where he can learn more about that profession and get paid at the same time. He didn’t need to look far.

A perfect “training” ground

Right there, not far from Ron’s hometown of Agra, stood the Jamalpur Locomotive Workshop, a 93-year-old institution that was to become the largest full-fledged railroad workshop in India.

During its early days of steam power, the facility repaired and assembled locomotives for the East Indian Railway. But by  1900, it was producing its own products. The railways became critical to travel throughout India, and by 1947, that industry was enormous.

1900, it was producing its own products. The railways became critical to travel throughout India, and by 1947, that industry was enormous.

That’s where Ron went to learn, serving as an apprentice. “In 10 years there, I learned a little bit about every trade,” he said. “Jamalpur manufactured everything except the boiler and the frame.

This extensive hands-on education served him well in his next job.

On to Calcutta, Tiffin and Phoenix

After a decade in Jamalpur, Ron found a job in Calcutta with a company that imported machine tools. Among those imports were bolt makers and forging presses from The National Machinery Company in the United States.

“After some years, National Machinery asked me to work directly for them in America,” Ron said.

That opportunity brought him to this nation’s middle—to Tiffin, Ohio—a move that changed his life completely, in an unexpected way. Ron looked forward to his American employment, and he settled into Tiffin. Everything seemed fine there until winter arrived.

“I was a man from India, from a semi-tropical climate,” Ron said. “I enjoyed my job and the people there. I stayed five years. But the weather? It damn near killed me! I had a friend from India who had started a little heat-treating business in Phoenix. The weather sounded great. I made the move and found a permanent home.”

The early years

In Phoenix, one heat-treating company customer indirectly brought Ron to the Valley Forge business he would later establish.

“One of our best customers in heat-treating was Karsten Solheim, a grand gentleman who had pioneered the Ping golf putter,” Ron said. “Our business was struggling, so he paid off our loans and bought us out.”

During the gas crunch in the fall of 1974, Ron found a little warehouse where he started Valley Forge. At the time, he was 44 years old. He started with two old forging machines, which he rebuilt, and a couple of ancient gas slot furnaces. He really had almost no financing—only a few hundred dollars.

“At first, we just specialized in forging liner bolts,” Ron said. “We would go to mines and try to sell them bolts. However, they were getting their bolts by the truckload from a major steel company.”

Fortunately for Ron, that steel company got out of the bolt business, and the mines were glad to have a local supplier.

Their product expanded from liner bolts to include special bolts. Ron realized early that he could only survive by making special bolts and providing technical services to customers. His wife Philomena handled the sales and finance while raising three girls and a boy.

The company today

In 2014, Valley Forge & Bolt Manufacturing Company is a model of efficiency, quality, and quick response to client needs, providing state-of-the-art fasteners and services.

The company provides extensive service and product advice to the oil and gas, construction, mining, and wind industries.

The company provides extensive service and product advice to the oil and gas, construction, mining, and wind industries.

“The patented Ridgeback liner bolt is our major product today,”

Ron said. “The ridges along the taper of the bolt plastically deform during assembly to take the individual shape of the tapered liner seat. A firmly seated bolt creates a solid surface to tighten against, reducing or eliminating the need to retighten bolts. This can save hours of expensive downtime.”

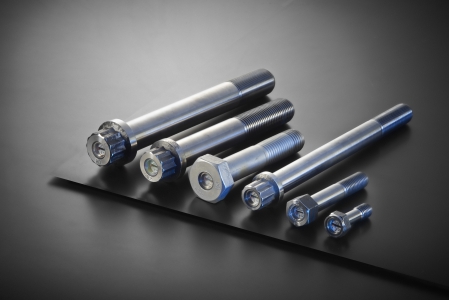

Valley Forge’s Patented Maxbolt load-indicating fasteners also serve all these industries. The product continuously displays the amount of tension in a bolt or stud and comes in various shapes and sizes.

Another featured item in Valley Forge’s current line is the patented SPC4 load-indicating fastener. It allows the user to constantly monitor the clamp load on the bolted joint, whether static or dynamic, by attaching a probe to the datum disc located on one end of the fastener and reading the value on a handheld, battery-powered digital monitor.

Valley Forge’s future

“The future in the fastener industry is bright,” Ron said. “We will see much more load-indicating and remote bolt load monitoring. The future also includes the use of exotic materials and a major shift to smaller diameter, higher strength fasteners. Right now, we’re also looking into special glues and jointing. The industry is changing quickly and growing.”

For the last 67 years, Ron Clarke’s ability to adapt—creating new products for growing markets—has built his reputation as a skilled engineer, innovative thinker and industry leader.

Reprint Courtesy of American Fastener Journal

| By Rusty Flocken |

The process cycle of fasteners is an interesting one. Consider this: Fasteners are manufactured from metals produced by tightly controlled, stringent specifications. Melting methods, chemistry makeup, cleanliness, and numerous mechanical capability tests are performed to ensure the steel mill makes material that is suitable for its intended use. From there, the fastener manufacturer closely monitors the processes of forging, heat treatment, dimensional machining, non-destructive testing, and threading to ensure ALL design parameters are met. Quality is assured through grain flow inspections, mechanical testing, precision measurement, surface and sub-surface non-destructive evaluations, carburization and decarburization inspections—to name a few. All of these controls are critical to ensure the goal of product performance is met so it may satisfy its intended purpose.

One often-overlooked or underestimated aspect of this process cycle is installation and tightening of the fastener. In fastening, joint tightness is nearly always associated with the use of a calibrated torque wrench during installation. For any given fastener, the relationship between applied torque and resulting tension is anything but direct. Many end users and installers seem to be aware of this fact, and yet they are content with this in spite of continued joint issues. The perceived connection between torque and accurate joint load is strong but unsupported. Installation torque is not a measure of joint tension. It is purely a measurement of applied tightening effort.

The modern use of torque measurement for the installation of  threaded fasteners has been in practice since the early 20th century. Conventionally, torque measurement has been the most practical means to control fastener tightness. Torque measurement is convenient in modern industry because many calibrated tightening tools are readily available. This practice of torque measurement has led industry to focus more on the use of special tightening tools rather than the fasteners themselves. An advantage of this focus is that any type of threaded fastener can be tightened with an appropriately selected torque tool without modification. There are many bolted/screwed joints where tightness is of limited importance, and they may not require any degree of control or monitoring. For joints in which tightness is critical, measurement of applied torque may result in joint loads that fall short of meeting actual joint requirements. There are several reasons for this, one being the influence of friction. When a fastener is tightened to a prescribed torque, this value has been calculated using a targeted clamp load and a nut (friction) factor. Information such as base material used in the joint, bolting materials, and any lubricants used are considered in the calculation. Complications can arise at random, with multiple fasteners from the same lot developing varying amounts of friction due to natural surface imperfections. Even within specification limits, variances in hardness and or material properties can also impact performance. Organizations that use equipment with tension-critical or problematic joints expend considerable time and effort in achieving accurately loaded joints. Available methods for measuring bolt tension include hydraulic tensioning, length measurement, direct tension indicators, and load-indicating fasteners. Hydraulic tensioning results in accurate application of tension during installation; however, nut placement, embedment, and relaxation can leave resulting joint load in question. Length measurement has been used for many years with gun drilling through the length of the fastener or with ultrasonic equipment. Both length measurement techniques are accurate, but each requires extensive machining and operator training for consistent results. Products classified as direct tension indicators are capable of providing subjective load verifications but cannot display numerical load values. Load-indicating fasteners are capable of showing real-time fastener load up to the material yield strength.

threaded fasteners has been in practice since the early 20th century. Conventionally, torque measurement has been the most practical means to control fastener tightness. Torque measurement is convenient in modern industry because many calibrated tightening tools are readily available. This practice of torque measurement has led industry to focus more on the use of special tightening tools rather than the fasteners themselves. An advantage of this focus is that any type of threaded fastener can be tightened with an appropriately selected torque tool without modification. There are many bolted/screwed joints where tightness is of limited importance, and they may not require any degree of control or monitoring. For joints in which tightness is critical, measurement of applied torque may result in joint loads that fall short of meeting actual joint requirements. There are several reasons for this, one being the influence of friction. When a fastener is tightened to a prescribed torque, this value has been calculated using a targeted clamp load and a nut (friction) factor. Information such as base material used in the joint, bolting materials, and any lubricants used are considered in the calculation. Complications can arise at random, with multiple fasteners from the same lot developing varying amounts of friction due to natural surface imperfections. Even within specification limits, variances in hardness and or material properties can also impact performance. Organizations that use equipment with tension-critical or problematic joints expend considerable time and effort in achieving accurately loaded joints. Available methods for measuring bolt tension include hydraulic tensioning, length measurement, direct tension indicators, and load-indicating fasteners. Hydraulic tensioning results in accurate application of tension during installation; however, nut placement, embedment, and relaxation can leave resulting joint load in question. Length measurement has been used for many years with gun drilling through the length of the fastener or with ultrasonic equipment. Both length measurement techniques are accurate, but each requires extensive machining and operator training for consistent results. Products classified as direct tension indicators are capable of providing subjective load verifications but cannot display numerical load values. Load-indicating fasteners are capable of showing real-time fastener load up to the material yield strength.

Load-indicating fasteners have historically been used in the most critical, problematic or specialty joints. All of the drawbacks of torque and tension tightening methods are no longer issues when standard fasteners are converted to, or replaced by, load-indicating fasteners. In fastening applications where joint tension is controlled, the only direct means to do so is with a load-indicating fastener. The coming model of reducing manufacturing and retrofit costs of load-indicating fasteners is creating a more cost effective solution for less critical joints.

Load-indicating fasteners have historically been used in the most critical, problematic or specialty joints. All of the drawbacks of torque and tension tightening methods are no longer issues when standard fasteners are converted to, or replaced by, load-indicating fasteners. In fastening applications where joint tension is controlled, the only direct means to do so is with a load-indicating fastener. The coming model of reducing manufacturing and retrofit costs of load-indicating fasteners is creating a more cost effective solution for less critical joints.

Valley Forge & Bolt Mfg. Co. has been manufacturing quality standard and custom fasteners for 40 years. For more than 15 years, Valley Forge has been leading the market with comprehensive bolting solutions using patented load-indicating fastener designs. Valley Forge load-indicating fasteners were one of the influences for the creation of the ASTM F2482 standard specification covering such products.

Rusty Flocken is a mechanical engineer with Valley Forge & Bolt Mfg. Co. in Phoenix, Arizona. He holds a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Arizona. His professional interests are robotics, material science, manufacturing automation, and fastener technology.